"Born to Run" 50th Anniversary Symposium, Part 1

Part 1!

\In case you missed it, I wrote a shorter, more general piece about the symposium for Variety.

“I’ve always wanted to do this,” said Robert Santelli, at the end of a very long Saturday. “Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band!” And then, in this 700 seat university theatre with terrible sightlines, there was E Street: Bruce, carrying “guitar #1,” the guitar he played on Born to Run, Max Weinberg, Garry Tallent, Roy Bittan, and Steve Van Zandt, along with Ed Manion, David Sancious, and Ernest “Boom” Carter, playing “Thunder Road.”

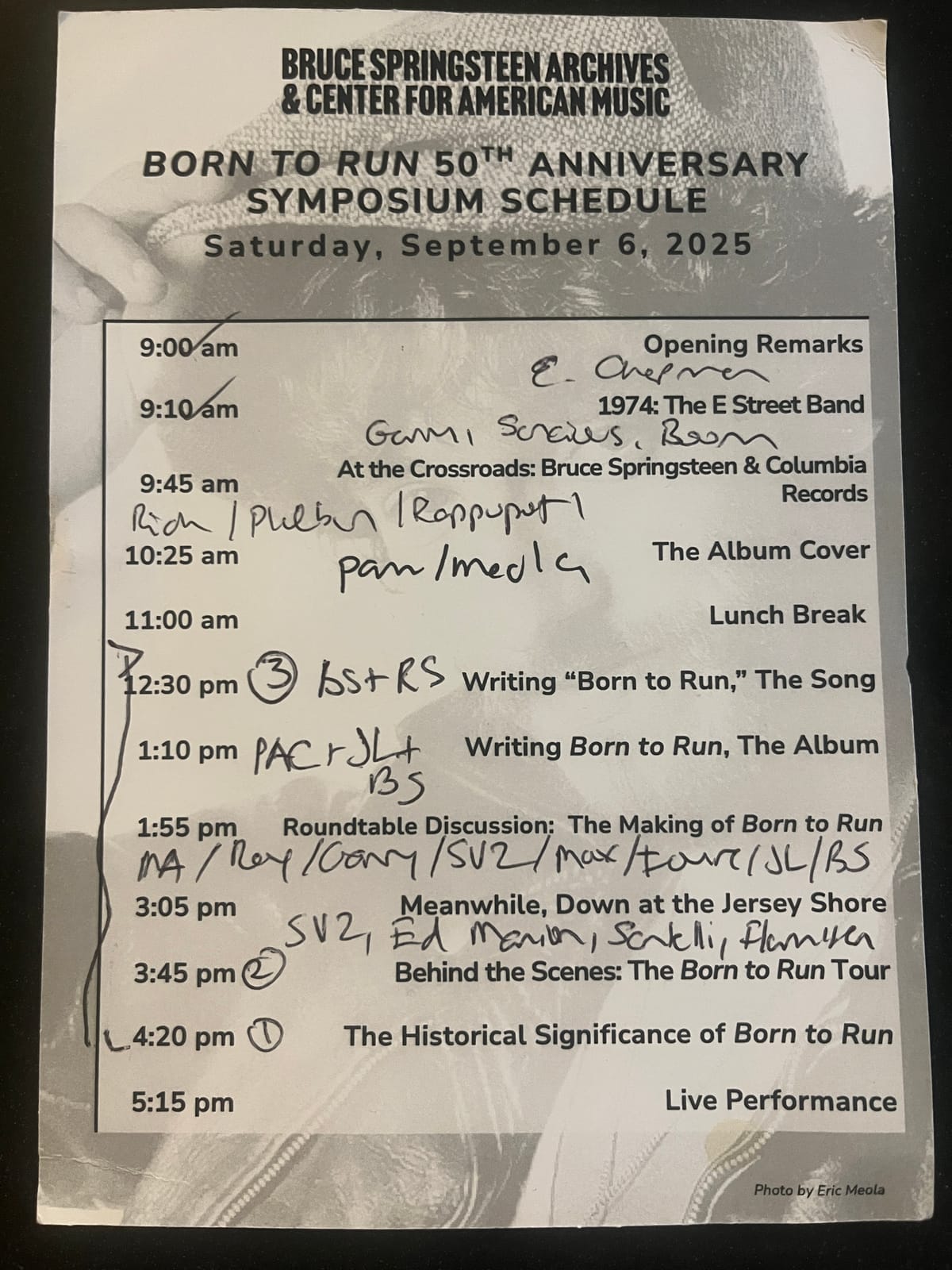

The symposium schedule, handed out Saturday morning, listed “Live Performance” in the last slot of the day, and we were informed that we’d once again be required to put our phones in Yondr pouches. If that didn’t make your spidey senses tingle, the large, draped mass of items along the back of the stage kind of clued you in that this wasn’t going to be a moment where Bruce pulled out the Takamine and played a couple of songs acoustically. But we also didn’t know for sure it would all happen until it did.

You know these songs so well, sometimes it doesn’t feel like they are being performed so much as you’re just turning up the volume of the radio in your brain just a little bit louder. It didn’t seem real, or possible, that you were watching an electric, full band version of both “Thunder Road” and then “Born to Run” in a tiny theater on a Saturday afternoon. Bruce held out the microphone at the usual line but we would have sung the line anyway; we were already singing along at the top of our lungs. The actual house with the actual screen door that slammed was just a little over two miles away from where we stood.

Everyone was on their feet. I was in the front row of the loge (which was just a slightly upper section across a larger aisle from the orchestra) and standing to my left in the walkway was Mike Appel and to my right was Jon Landau. This was the oddest and most fascinating scenario to find myself in, but also? I did not want any distractions from what was going on onstage. This was my only chance to see the E Street Band live in 2025. I wanted time to stand still. I have never wanted to appear in a version of Groundhog Day as much as I did at that moment.

“Born to Run” was “Born to Run.” It is always anthemic, always cathartic, never dull, never tired, never boring. You slip into the song like an old flannel shirt. You know every word, every note, every second, when to put your arms in the air, when you need to bring your sing-a-long A game. I watched Max and Boom Carter play together, the only song that Boom ever got to record with the band, the song that Max has now played probably close to 1,500 times*. I wish I could tell you that I could clearly hear everything Davey Sancious was playing but it was all a gigantic, blinding flash of light and energy and emotion.

*The math: Brucebase says that “Born to Run” has been performed 1,868 times. Taking out Springsteen on Broadway (238 performances) and some rounding for times that Bruce has played it solo got me to that number.

I thought of the Hold Steady lyric, “Our psalms are sing-a-long songs” and how that has always been true but never truer for me than right here, right now. It is a profession of faith, it is a declaration of hope and an assertion of liberation. It was the song that told you you were going to make it, that you would get out, that you would survive. It is the song that asks the most essential, most vital, and most fundamental question in all of Bruce Springsteen’s work: I want to know if love is wild / I want to know if love is real. And almost everything that happened before this moment on Saturday affirmed the answer to that.

Here's more detail on some of the most interesting panels of the day. The Springsteen-attended panels will get their own post.

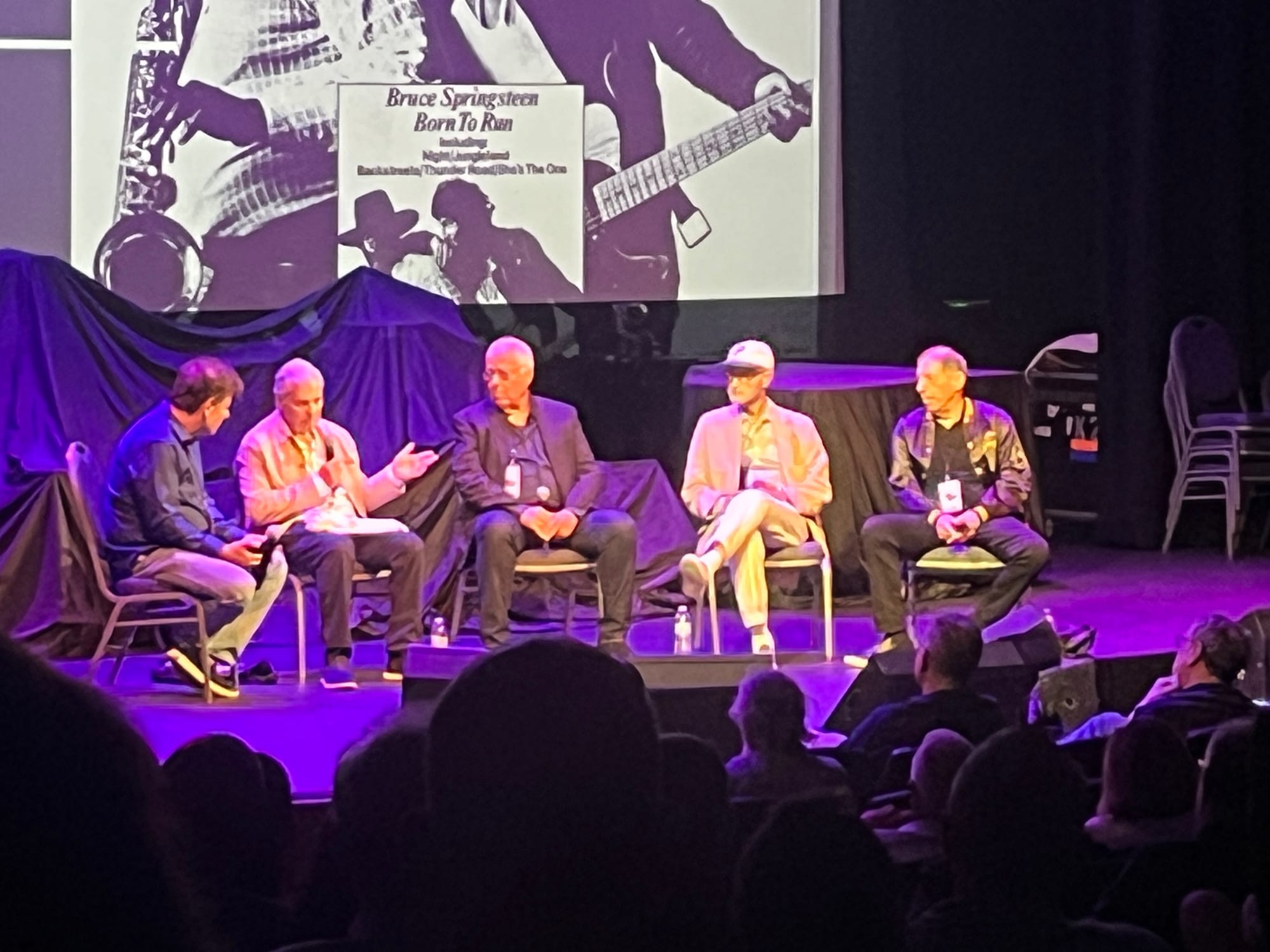

1974: The E Street Band

Moderator: Tom Cunningham

Participants: Ernest “Boom” Carter, David Sancious, Garry Tallent

DJ Tom Cunningham came prepared with a binder of information taken from Brucebase, where he began by letting us know that the lineup with these gentlemen only performed 88 times. Unfortunately, “Boom” Carter didn’t have any recollections to share. As David Sancious put it, “You have to appreciate that this is quite a lot of years ago, and when you’re doing it, you’re not really concentrating on holding onto your memories to talk about them later.”

Which led to this exchange:

Tom Cunningham: “Dave, what do you remember about the early versions of ‘Jungleland’?”

David Sancious: “Hmm, not much.”

or this:

Tom Cunningham: “Garry, what do you remember about playing ‘Born to Run’ live in those early days?”

Garry Tallent: “Absolutely nothing.”

Cunningham: “Garry, the auditions were held at your father’s house, in the garage. Garage rock at its finest. Was it a big garage, and what was the setup like?”

Tallent: “It had no heat, and this was February.”

I do not blame the moderator or the panelists for this scenario. You don’t always get a chance to speak with the other people on the panel in advance and clearly that was the case here. But there have been two previous Springsteen symposia and surely someone could have assessed the situation for this panel and given everyone a better chance of success.

At the Crossroads: Bruce Springsteen & Columbia Records

Moderator: Rich Russo

Panelists: Mike Appel, Peter Philbin, Michael Pillot, Paul Rappaport

This panel should have been twice as long as it was.

Peter Philbin was the director of global publicity and later became Bruce’s A&R guy. Michael Pillot was the head of album promotion in New York (and “the man who got us ‘The Fever’ on the radio”) and Paul Rappaport was the head of West Coast promotion. Rappaport showed up wearing the promotional satin baseball jacket for the album; it was in pristine condition. Much respect.

These were some of the people who kept Bruce Springsteen alive within Columbia Records. They were young guys who absolutely loved him and they were going to do everything within their power to keep him on the label and make him successful. As Philbin explained, “We were advocates for Bruce. We were a lot younger. As Peter Carlin says in his book, it was like a religion.”

Rappaport continued, “The big story is, that a lot of people don’t know, is that there’s this core, four of us were fighting our own label because they’re selling Barbra Streisand, Neil Diamond, Paul Simon, these big money makers and then Bruce is sort of down here and some of us have seen him. So we’re like, you better pay attention to this guy. So it should be known that not only were we promoting him on the radio, but we’re getting the higher ups to pay attention. We’re fighting them for money, for live broadcasts, for news, for anything, and telling them, ‘You better pay attention to this guy.’”

Philbin mentioned that there were other people at the label who were passionate about other acts, and that now that he looks back on things, the system worked well, even if he wasn’t so happy at the moment, he was happy now.

“Mike, were you happy?” he asked Appel.

“No, I wasn’t,” Appel predictably answered. “Everything they said was untrue. These guys were friends, they were not adversaries.” Appel then explains that they were fighting the changing of the guard at Columbia, when Clive Davis was fired. There was then a whole fascinating digression of how Rick Springfield tanked his own career and how there was confusion between Springsteen and Springfield.

But of course, Appel has a much different perspective than the ex-Columbia Records staffers, and it is both hilarious and endearing that he’s still angry about these perceived slights to his artist that happened over 50 years ago. This isn’t the only panel Appel was on, but each appearance only further reinforced that opinion. He is absolutely still as brash and outspoken and tirelessly defensive of his efforts to promote his artist.

“Mike and I talk about this occasionally. And I was pointing out that Bruce at this point was in his formative stage, and when I said to Mike, ‘You know, some of the shows weren’t as good as the others,’ Mike Appel thinks that Bruce Springsteen never played a bad show.”

Appel: “That’s correct.” He gestures at the audience in front of him. “Obviously, I’m right.”

There was a long discussion about how “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” was a single and that listeners in Texas -- “Bruce was thrilled that guys with cowboy hats were listening to his music,” shared Philbin -- were not delighted by this choice, and would send postcards to the radio station asking them to please stop playing the song. Paul Rappaport was at the CBS convention in San Francisco where he got to see Bruce for the first time.

“I'm sitting way in the back because I'm working at the Houston, Texas branch and I'm dying to see Bruce Springsteen because we had an outrageous amount of airplay in Texas. So I just got up and I walked my snake my way through this conference room at the hotel where we're doing the convention and I sat right in front of Bruce Springsteen. And he walks out. He's playing acoustic guitar. Gary's playing tuba. And Clarence is playing saxophone. And I went, now we're talking, because I love ‘Wild Billy’s Circus Story.’”

It was a master class in the way the music business used to work. But also? It explains everything about how Bruce Springsteen survived and later thrived. Peter Philbin said, “The most important thing I think in selling an artist is taking people far enough so they can find it for themselves. I’m sure most of the people here have a specific memory of when they saw Bruce. For me, the way to promote Bruce was to get people into the show and leave them alone and let it be their personal experience with Bruce. That was the best way to break Bruce Springsteen.”

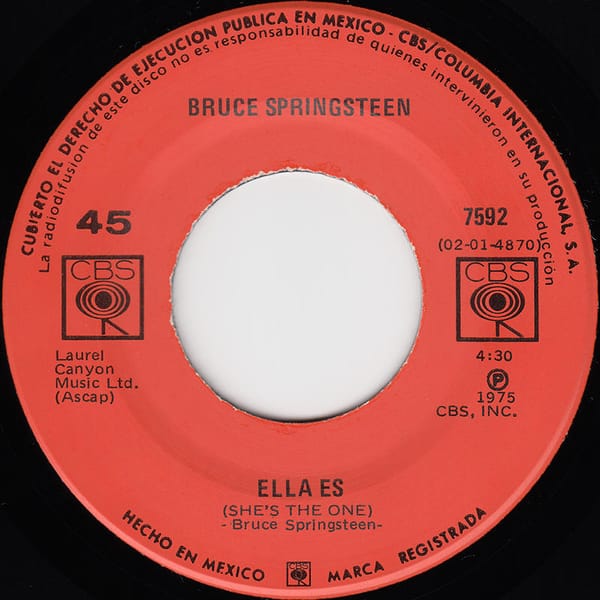

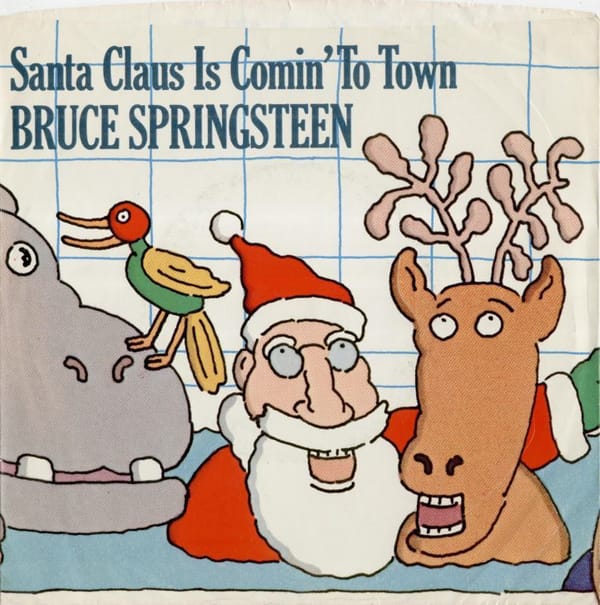

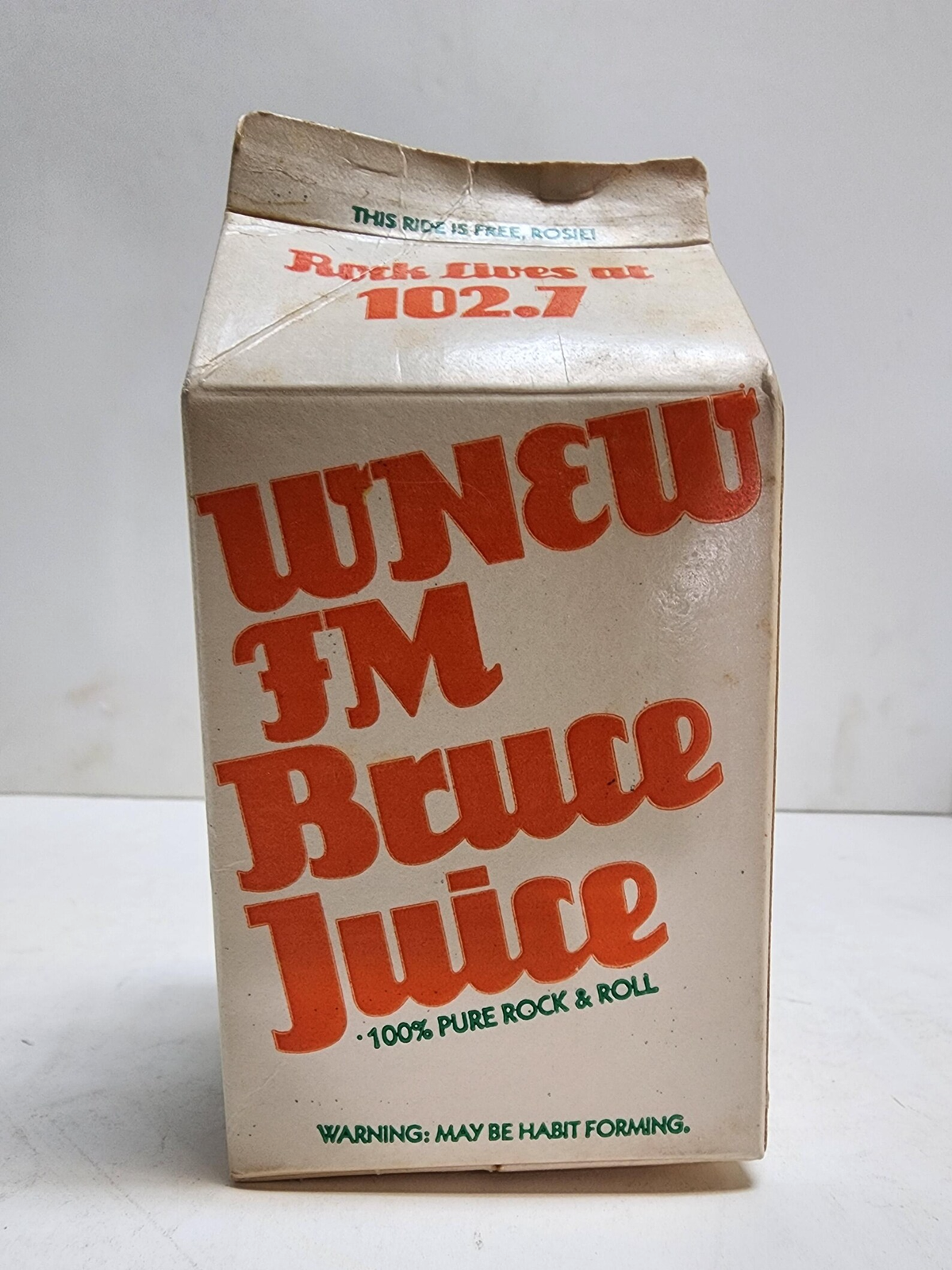

The last story from this panel that’s not new but absolutely worth telling is Mike Appel sending Christmas stockings full of coal to radio stations that weren’t playing him in 1974, especially to Scott Muni, the program director at WNEW-FM in New York.

Appel: “We sent them all out and they hated my guts for doing that.”

Russo: “How did that affect your job when radio stations are getting coal?”

Appel: “Who cares? I’m promoting an artist.”

Paul Rappaport has a book out called Gliders Over Hollywood and I read the chapter where he talks about the Roxy broadcast (which we’ll get to in October) but after this panel I am excited to read the whole thing. (Rappaport also sat down with Flynn McLean & Hal Schwartz over at None But The Brave a couple of months back.)

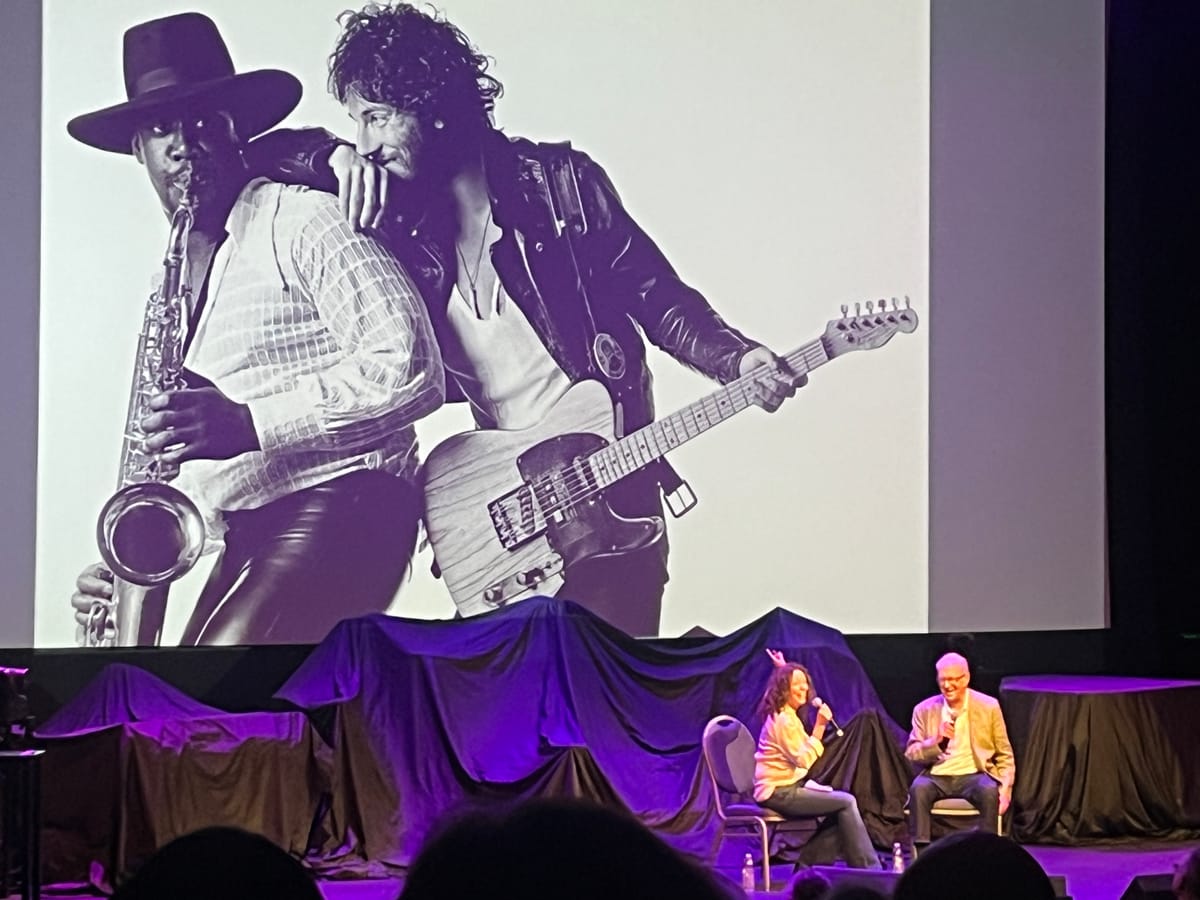

The Album Cover

Moderator: Pam Springsteen

Panelist: Eric Meola

What an absolute delight this was. It was warm and thoughtful, and although there were no gigantic new revelations, Pam got Meola to open up a little bit more than he might have otherwise because she was both a photographer and because she was Bruce’s sister. So when Meola explained that when he went down to Red Bank to see Bruce play and Clarence walked up to him after soundcheck and said, “Let’s go get a beer,” and Pam came back to ask, “Do you want to tell us about Clarence at the bar?” he truthfully answered “We had too many beers… I had one. or two. Okay, three.” We also learned that the collector who ended up with the postcard originally reached out to Meola and offered it to him for $5,000.

But he also said this about why the cover was in black and white. “I said, ‘It’s gonna be black and white,’ and he questioned me about that one…I said, well, color distracts, your eye goes to the color first, and we’re gonna sit here talking about are you wearing a green shirt? That kind of thing. Let’s stick to black and white. Black and white is rock and roll.

Meola also noted that Mike Batlan walked in with props and that it was at that moment, “...It dawned on me that Bruce had really thought this out himself, and this is an important ting -- in terms of what we were photographing, that what we were photographing was something that would telegraph who they were and that was the whole point with the guitar and the saxophone.”

“I’m sure he looked at that tank top the night before and ripped it.”

“I think he got it at the Goodwill,” the younger sister responded.

Another a ha moment was Pam’s technical assessment of the work: “I just want to point out that this image seems simple, shot on a white backdrop, and it is one of the most technically difficult things to pull off. Well, in the age of film, he's got manual focus. He has his two subjects. One needs a stop more light than the other one. He's got shiny instruments. He's got a height difference and then they throw in a hat. This is not easy.”

Meola also noted that the guy who wanted to sell him the postcard bought the fret guard from the guitar for $50,000.

Towards the end, Pam also noted, “So I just have to say this though, because we've talked a lot about technically what went into it, the things that were brought to the shoot. But when you look at this image, it transcends all of that. And the powerful message that you captured in this one fraction of a second is our 1+1=3.”

A small reminder here that Eric Meola’s exhibit of the photos from the Born to Run sessions is free and open to the public at Monmouth University until December 18, 2025.