"Born to Run" 50th Anniversary Symposium, Part 2

Part 2.

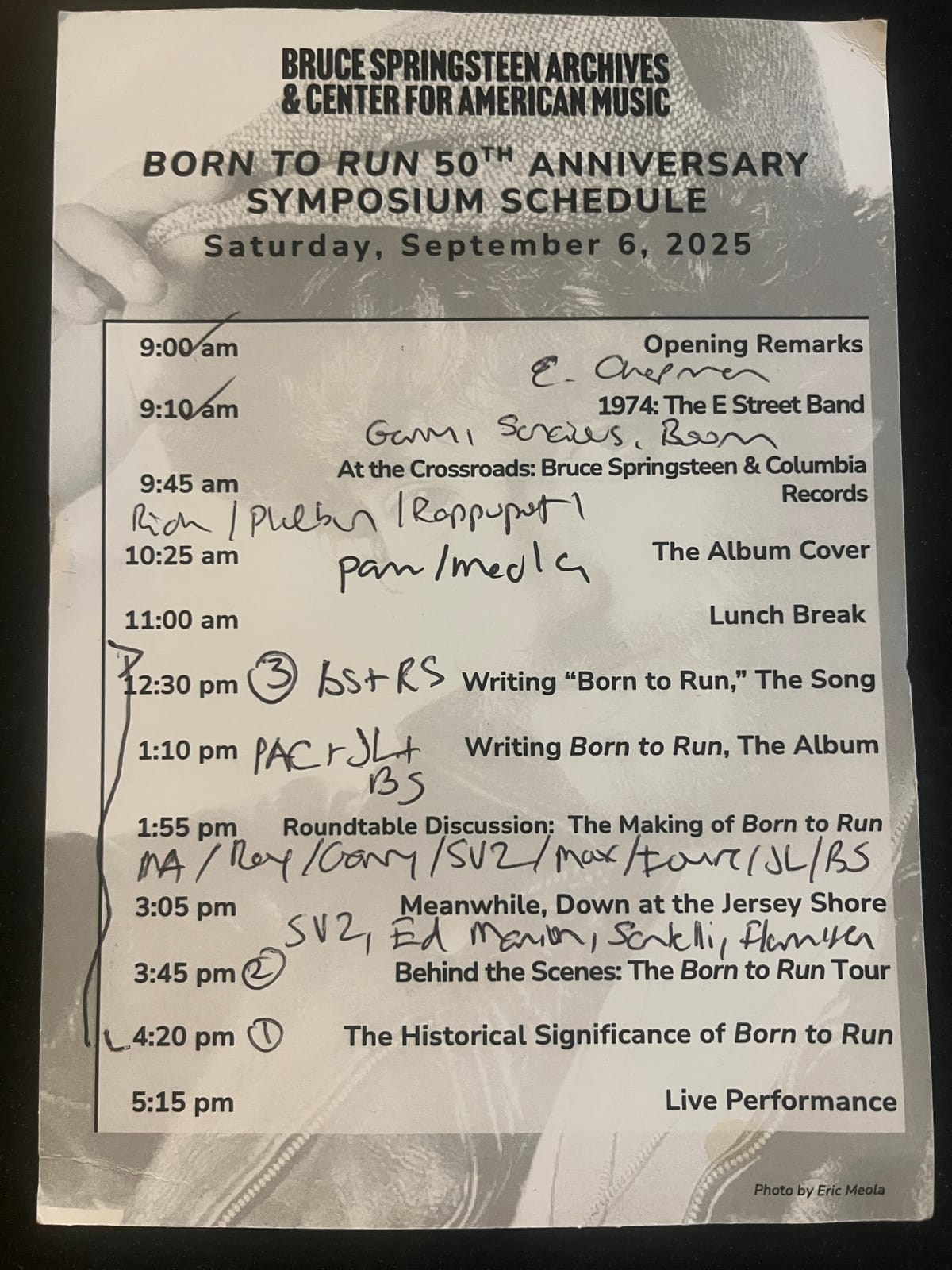

The heart of the afternoon, post-lunch/post-Yondr lockdown panels boiled down to a series of deep dives on writing and recording Born to Run. We had “The Writing of ‘Born to Run,’ The Song,” “The Writing of Born to Run, The Album,” and then “Roundtable Discussion: The Making of Born to Run.” Bruce Springsteen was present and participating in all three, which was absolutely phenomenal. He had great recall, he did not dodge questions – he did actually answer “no” to several of them – and he was 100% present and invested in the discussions.

For the first discussion, we still weren’t 100% sure what was going to happen but when the stage was cleared and two high bar stools were brought out, things seemed to be trending upwards. Bob Santelli made a remark about what better way to hear about the writing of the song than from the horse’s mouth, and out walked Bruce, in black pants/vest with a gray buttondown, sharply coiffed, and very ready to participate.

“I still don’t know where it came from,” he began, talking about the phrase ‘born to run.’ To this day he doesn’t know whether it was something he heard or saw painted on a car on the Circuit or similar. He also noted that when he heard that he’d only sold 20,000 copies of each of his first records, his first thought was, “Who are all these people buying that record??” because to him, that was an enormous number.

He talked about living at 7 ½ West End Court and how he was listening to all these records: “Because They’re Young” by Duane Eddy, Phil Spector, the Beach Boys “Don’t Worry Baby,” and that he used to go to a record store in the subway in New York City to buy oldies.

That statement made me almost fall off of my chair, because he’s talking about Times Square Records, which is a store that was also mentioned by Lenny Kaye in his 1970 essay “The Best of Acappella,” published in Jazz and Pop Magazine. This was the essay that prompted Patti Smith to reach out to Kaye and for the two to become friends, and later, bandmates. Times Square Records has a fairly infamous place in NYC music history and this is the first time I’ve heard Bruce specifically talk about going there to buy these records, one of a handful of places where you could find these kinds of oldies singles back then. (They even reissued some of the harder-to-find songs that later became more popular.)

Bruce spoke so movingly about his creative process. “I don’t want to sound like a retro act. I want something purely modern that speaks to the times.” It took him six months because he went line by line. He was balancing guys, cars, and girls -- “the basic subjects of rock and roll” -- with wanting to write something that offered hope. “I knew I had to move myself into what I was writing.”

He told a funny story about how when he was signed, he was signed as a solo artist and no one at Columbia or even Appel had seen him with the band. He noted that the first time Mike Appel saw him play live with the band, he commented, “Hey, you really know what you’re doing.” “Yes. I do.” We hear so much about Bruce’s inexperience in the studio or his fears that his label was going to drop him, and maybe some of this is a tiny bit of revisionist history, but was good to hear and see and feel the confidence he actually had in the music he was making.

Back then, Bruce wrote in spiral notebooks, and he affirmed that he still does. He told the story about how he taught himself to play piano on Aunt Dora’s spinet by figuring out how to transpose guitar notes into piano notes, and how she gave him a key to the house so that he could come by whenever he wanted to play the piano. Eventually, she gave it to him, and eventually, that piano came to the house in West Long Branch. The house in Long Branch is where he listened to the final, completed mix of “Born to Run” and finally felt like he’d done a good job: “Yeah. That’s how I fucking sound.”

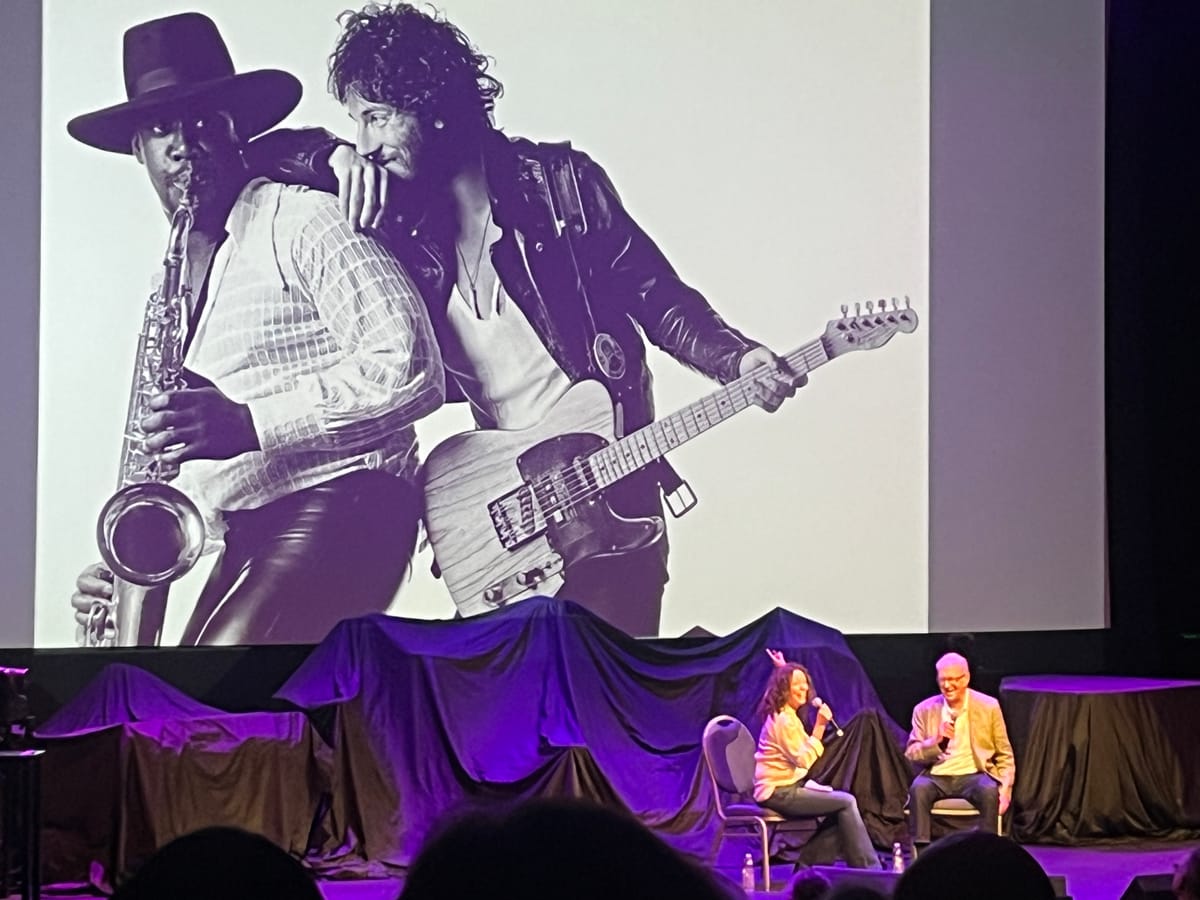

They swapped Santelli out for Peter Ames Carlin, author of Bruce as well as the new Tonight In Jungleland - The Making Of Born To Run for the discussion on the album, where Bruce returned to the stage along with Mr. Landau. This discussion unsurprisingly really turned into an analysis of the friendship between Bruce and Landau, and what that brought to his work. Landau admitted, “I was the anti Roy Orbison because I wanted to simplify (the record),” talking about how the first contribution he made was to suggest moving Clarence’s sax solo. Bruce joked, “I of course took it to extremes, which was my specialty,” but that his friendship with Jon Landau was based on the idea of, “Who has the information that’s going to take my work to another level?”

And then, of course, this:

“We were gonna make the greatest rock and roll record of all time.”

“That’s what we did.”

If they share nothing else, Jon Landau and Mike Appel were 100% believers in Bruce Springsteen, his talents and abilities.

In response to a question about lyrics for “Backstreets,” Bruce asked for the lyrics to go on some screen somewhere, and the easiest was to put them on the teleprompter at his feet. “I’m 76,” he explained. “I don’t know any of them.” When they finally came up, he read through them as they scrolled, and then declared, “That’s a good opening four lines.”

Carlin tried to get Bruce to agree that the characters in “Born to Run” and “Thunder Road” were autobiographical. Bruce said no. “I felt like I was writing characters.” He also refuted a question that was around the album being a concept record: “It’s not a concept record but it is conceptual,” he offered. He also admitted that the end of the record “...is a crucifixion of sorts,” and that the wail at the end of “Jungleland” finished the record, the song, the characters, and the story. “There was nothing else after that.” There was apparently shock in the control room when he was done, and Bruce admitted that the depth of emotion “was unexpected to me also.” And most importantly, Bruce once again asserted, “There wasn’t a note that I’d change or a lyric that I’d change,” at least now, and not a couple of weeks after the record was done and he was listening to it on a crappy portable turntable.

We did learn that Landau, however, was not a fan of “Tenth Avenue” at the time. “DId we think that ‘Tenth’ would be a through line? I thought it was a throwaway and I didn’t want it on the record.” Bruce countered with, “I didn’t realize I was writing the story of the band.”

Everyone left the stage and although I saw Stevie hovering towards the back of the audience chatting with Jimmy Iovine (a surprise for me as I had backchannel info that he was the one person who wouldn’t be there), I was absolutely not prepared for Santelli to come back out, announce the “Roundtable Discussion,” and introduce Roy Bittan. He was joined by Garry, Max, Steve, Bruce, Landau, Appel, and Jimmy Iovine. Iovine ended up being one of the highlights of the panel, because it was such a landmark event for him as well. He explained that he was the guy who played right field and prayed that no one hit the ball to him, until that moment he ended up in the studio with Bruce and the band. But they asked him if he thought he could mix the record and he somehow found the cajones to say, “Hit the ball to me.” He and Landau also explained how they used his tendency to fall asleep at the board in the middle of the night as a way to get Bruce to let the band call it a night: “Bruce, the engineer’s asleep. It’s time to go.”

Roy Bittan’s presence was absolutely delightful. He had nothing but positive and uplifting things to say about everyone. He talked about reading the Village Voice ad and seeing “everything from classical to Jerry Lee Lewis” and thinking, “That was exactly my wheelhouse.” Max also talked about his audition and how he knew he wanted the job about 10 seconds in. “Thank you for choosing me,” he said.

Of course, none of this got Garry Tallent’s memory to open up. I wrote about this in the Variety piece but it is just solid gold:

“Garry, do you have any perspective from the bass player?”

“It took forever.”

When pressed, he turned the mic back on and added, “It had to be done, so I did it.”

“THAT’S the bass player,” Bruce exclaimed.

Roy: “His playing was spectacular.”

I can never hear the story of Steve singing the charts to the Brecker Brothers too many times. Bruce began telling the story and my eyes didn’t leave Steve’s face, hoping for some kind of reaction. “These guys are screwing up my friend’s record,” he says was his driving thought, but otherwise, the story is pretty much as we understand it to be.

Bruce also told the story of someone at Columbia suggesting to him that they go into the studio that night with some session guys in order to see what the record really could be. Bruce’s reaction? “These were the people that I wanted. I didn’t want professionals. I wanted guys who would put their heart and souls on the line.”

While Iovine was mixing the record, he explained that it was a very, very dense recording, and when he got lost, he would look for Roy: “Whenever I got in trouble, I reached for Roy’s piano.” This mirrors something that he told Mike Campbell of the Heartbreakers, and it’s a quote that stood out to me from Campbell’s book, where the secret to making a song better when you worked with a keyboard player like Benmont Tench or Danny Federici was simple: turn them up.

I couldn’t find this quote in my notes when I was writing the Variety piece (in my defense, I basically filled a 70-page reporter’s notebook) but Iovine explained how everyone on the panel was responsible for helping him grow as a human being. “Taste, how to behave as a person, everything short of how to eat with a fork. These guys collectively taught me everything.”

Bruce: “These were the guys that were there when you needed them. When you were nothing and had no one, these were the guys who gave you everything.”

For the entire panel, there was a guitar sitting in the middle right next to Steve’s chair, and I kept wondering what it was there for. On cue, he begins to tell the story, and Bruce interrupts him: “This is the greatest contribution that Steve Van Zandt has ever made to my career,” which is a fairly definitive statement to make. And this will be the one element of the day that I wish I had audio or video for, because it’s hard to write about music notes.

Basically, Steve was hanging out at the studio and listening to “Born to Run” and said something about “the minor chord on the riff.” He demonstrated it, and you could clearly hear the difference – but no one in the studio could because they had heard it too many times. Bruce insisted that had Stevie not pointed this out to him, the record “would have been a total failure.” I’m not so sure I agree with that but we’ll take him at his word. He was right about a lot of other things.

The panel titled “Meanwhile, Down at the Jersey Shore” had the misfortune to be the panel between the roundtable and the Live Performance. But it ended up being one of the more interesting panels of the day, because it was SVZ, Ed Manion, and Bob Santelli, moderated by Erik Flannigan. Santelli was a musician back in the day so his perspective on the scene was insightful and valuable, but the star of this one was absolutely Steve Van Zandt. SVZ going long on how The Jukes were a dance band and this is why they were successful, and how his ideal horn section is five pieces – "That's my sound, baby." And Santelli observed that one of the things that Springsteen's popularity brought was the "look" of the "Asbury Sound" – leather jackets, boys with one earring, the newsboy cap.

The other two panels were “The Historical Significance of Born to Run” and “Behind the Scenes: The Born to Run Tour.” The first one did not offer anything new or interesting, and the latter could have been fascinating but was definitely another panel that suffered from not knowing in advance what people were or were not going to have to say about things. Barbara Pyle was the most interesting person (although I don’t know why she got shoved into this panel) and I would have gladly listened to her talk about her photography and being on the road with the band instead of what we did get.

Unlike Part 1, for this piece I had to rely on my written notes, because when we came back from lunch all recording devices were prohibited. I have a lot of thoughts about this; I am not sure that embargoing Bruce Springsteen talking about the record or even playing two of his most-performed songs with the band required this kind of lockdown. Especially because none of this material or information will be available to anyone to access for quite some time. It seems like a very anti-archivist stance to have taken.

Even if it’s just a random fan who wanted to record the panels for their own collection or for some kind of future project, why are we gatekeeping information that was presented in a public symposium? Many fans would like to have attended but were unable to travel, and even for those who were local or willing to travel, the ticket on-sale was a nightmare and I say that as a veteran ticket-buyer to Springsteen-related events.

On the other hand, I’m kind of grateful we weren’t looking at a wall of phones, the sight lines at the Pollak Theatre were bad enough. I also get that trying to enforce “no video” would have been challenging but it wouldn't have been impossible. But honestly, I don't understand why this event wasn't broadcast on the internet. People would have bought tickets to watch a livestream and would have paid for access to it after the fact. Every music fan should have had the opportunity to watch these panels.

The archives should be in their permanent home by the time we need to reconvene to celebrate Darkness on the Edge of Town in 2028 and I hope many of these issues are reconsidered.