Photographer Eric Meola Talks About His Springsteen Fandom and How He Ended Up Shooting The "Born to Run" Cover

"I remember thinking to myself, 'I've got to photograph this guy no matter what.' "

For anyone subscribed to this website, Eric Meola needs no introduction. He’s the photographer that captured one of the most indelible images not just in Springsteen fandom but in rock and roll history: the cover of the Born to Run album. His dramatic, black-and-white shot of Scooter and the Big Man defined and set the tone for the era that followed, and few covers have looked as good since.

That epic gatefold set a new standard in album covers; the image was immediately duplicated into thousands of bootleg posters that adorned college dorm rooms. The live version of that image was the first thing millions of television viewers saw at the XLIII Superbowl halftime show in 2009. I even have a small excerpt from that shoot -- the sneakers hanging off of the guitar headstock -- tattooed on my left forearm and I know I’m not the only Springsteen fan who’s done something similar.

I’ve always wondered about Meola’s inspiration for the images and how he ended up being the photographer who got the call. Graciously, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the creation of that artwork that looms so large in all of our legends, he agreed to let me interrogate him and where we went long on his Springsteen fandom across the decades (he is a frequent Brucebase user!), and learned that a lot of what I thought I knew – or had assumed – about this image that has followed me for most of my life had a much different story. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I kind of want to get the chronology of you getting to June 20, 1975. (The day he shot the cover.)

So we’re talking early 70s and I was living alone At 134 Fifth Avenue. I was one of those people, one of those 15,000 people who, you know, bought the first two albums. And, you know, there were a few songs I didn't like on there but for the most part, I was knocked out. And I had a real sense because I think even then, That plus my own sense of the music was compelling. And I used to, you know, listen to those songs quite a bit.

But how did you even hear about the records? Because one thing I read mentioned that "Growin' Up" was kind of your aha moment. Is that correct?

Yeah, you know, it was such a simplistic melody, you know, that da da da da da da da da da da. I was still at that stage of my life where I was trying to figure out who was I, where was I, where was I gonna go, what was life all about? You know, the questions we ask ourselves throughout life. But I had recently gotten divorced and I think that weighed on me a bit. And I was very much in love with Dan Kramer, Daniel Kramer's photographs of Bob Dylan.

And my own career was starting to take off. I had done a number of large jobs and I had photographed Beverly Sills for the cover of Time Magazine. I'd photographed a number of famous artists in Soho, and my career was taking off, and I heard this, I guess I must have, it's going a long way back, but I for sure I heard it on the radio. I probably heard "Blinded by the Light." And "Fourth of July, Asbury Park" blew me away. "Mary Queen of Arkansas" was my most hated, and remains my most hated song of Bruce's.

Preach.

And all the stuff we know about Bruce now, in terms of everything from his father to the fact that he was in other bands. I never thought about where he came from. I mean, I obviously knew that he came from the Asbury Park area, Freehold, but I didn't really think much about where he came from. And one day, I happened to be walking by Max's Kansas City. This would have been early 1973, and I saw signs on the window saying that Bruce was going to be there. And that was one of the Bob Marley concerts, you know, Bruce and Bob Marley.

That was going to be my next question: which Max's show? So now we've narrowed it down.

I can’t narrow it down.

But it being one of the Bob Marley shows, that does narrow it down.

So I went to see him and one of the shows, I wonder what I was thinking because he was a very shy guy and he did not have the delivery that he has now. But he must have had something because I was, I remember thinking to myself very strongly, 'I've got to photograph this guy no matter what.' And of course I was busy. You say those things to yourself and you don't do them. And a year goes by. I saw him at the Bottom Line in ‘74 and that was an amazing show. I had brought a girlfriend along at the time and we were both blown away. And then he was going to play at Central Park that summer. Now I'm really getting my dates mixed up, but I went down to Red Bank, New Jersey.

I'll quote you back to you if it helps. You talk about how you ran into Bruce on the corner of Central Park South and 5th Avenue under an awning, which was probably right where the subway comes out under the Plaza, which is where everyone met if it was raining and you were going to a show at Wollman (Rink). You ran into him because he was on his way there, and when I read that I was like – 'wait, is that the Anne Murray show?' Of course it was the Anne Murray show. So were you not going to that show? You just happened to run into him?

Well, no, I went to the show.

Okay. Of course.

I was not photographing him at this point. I wasn't really into photographing musicians at concerts per se. I don't have a strong sensibility about journalism, which is a big fault of mine, I will admit. I love journalism, photojournalism, but it wasn't my thing.

So I ran into him and I was on the steps and starting to go up and someone was in my way and I looked up and it was him. And he saw that moment of recognition in my face and sort of looked at me like, so what do you wanna ask me? And the lyrics on the Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle were not on the album. I've spoken with Michael Appel about that and Bruce actually together, when they were at Clarence's wake, and we had a moment together and as awkward as it was, that was one of the questions I asked. And they both shot back that it was a mutual decision, that it was like an experiment, you know?

I don't remember what song it was. “New York City Serenade” possibly. And I sort of mumbled off the leading lines, and then Bruce came in and told me what the lyrics were. And that was about it. He asked if I was going to the show and I said, of course. And he went on his way and I went on my way.

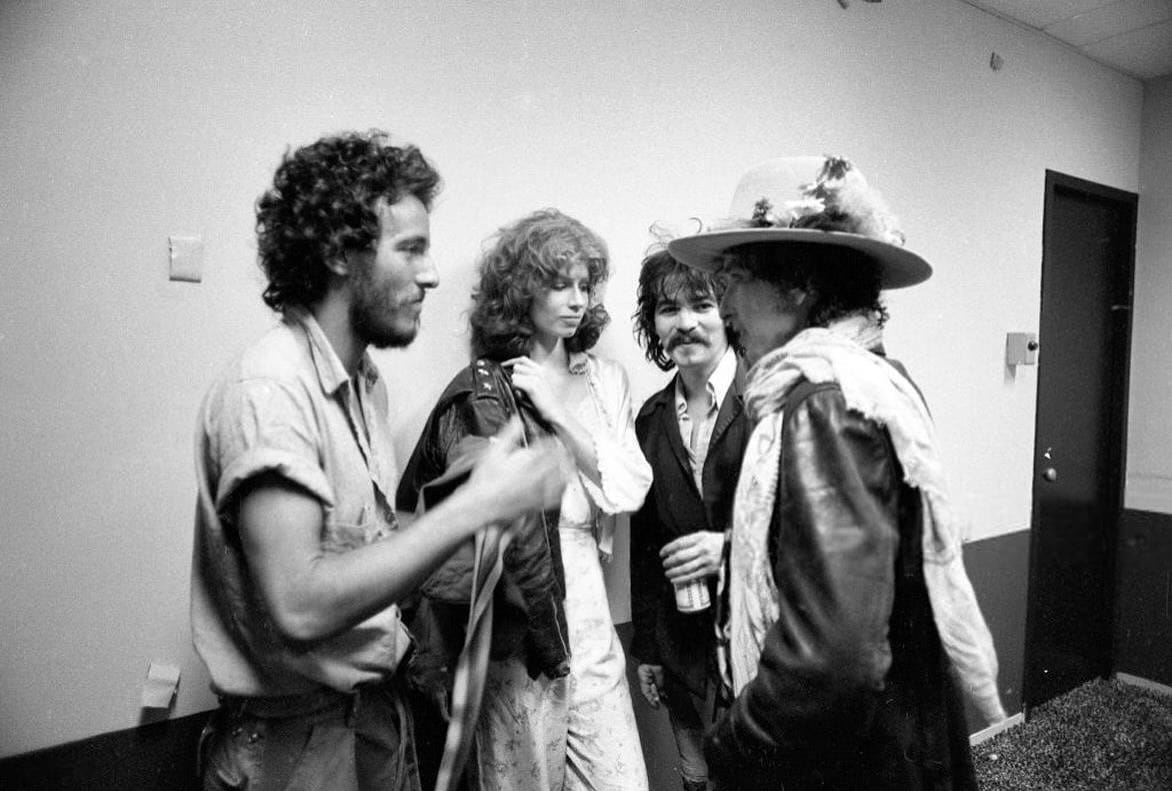

And a few weeks later, I went down to Red Bank. I went with my friend to that show (8/14/74) and we got there early. And Mike Appel was standing outside. He had his Marine drill sergeant hat on, and we got in, it was like five bucks or so or something to get in, and there was an orchestra pit, and we sat in the orchestra pit, and Bruce walked in, and we'd just seen each other a couple of weeks earlier and he recognized me, and we talked for a bit. He came over and said hello, and then Clarence came in and they were doing a sound check and that's how we had our first sort of real talk. And then I remember we went backstage afterwards. I don't remember much about it. Met Danny, met Garry, and that was about it.

And then it becomes a blur. I must've gone to, you know, 15 or 20 shows from Connecticut to New Jersey to New York.

And you don't have a car, so this is a real commitment back then. As someone who also lived in the city and didn’t have a car.

Well, you know, I rented a car, so yes, it was a real commitment.

So the more that I got to know Clarence, and I used to hang out at Clarence's house and Bruce would come over occasionally down in Sea Bright, and we got to know each other and talk. I was taking some pictures of Clarence at that point. And as I said, there were so many shows that it becomes a blur, without Brucebase in hand, I couldn't tell you.

But at some point, you know, I realized very strongly that there was this album called Born to Run that he was working on because by then, he was doing rough versions of several of the songs. I had contacted Mike Appel at that point and I would hang out at his office and then Bruce would come by.

I remember being at Mike's office one day and he called someone on the phone and he was talking about – this is so hard to imagine – 'Bruce just called me up and he was talking to me about this song called "Tenth Avenue Freeze Out" that he just wrote on the bus.' "Tenth Avenue Freeze Out," he's going on and on and I'm imagining Bruce on the bus, just somehow writing "Tenth Avenue Freeze Out" and calling Mike all excited. I mean, those were the days, that's what it was like.

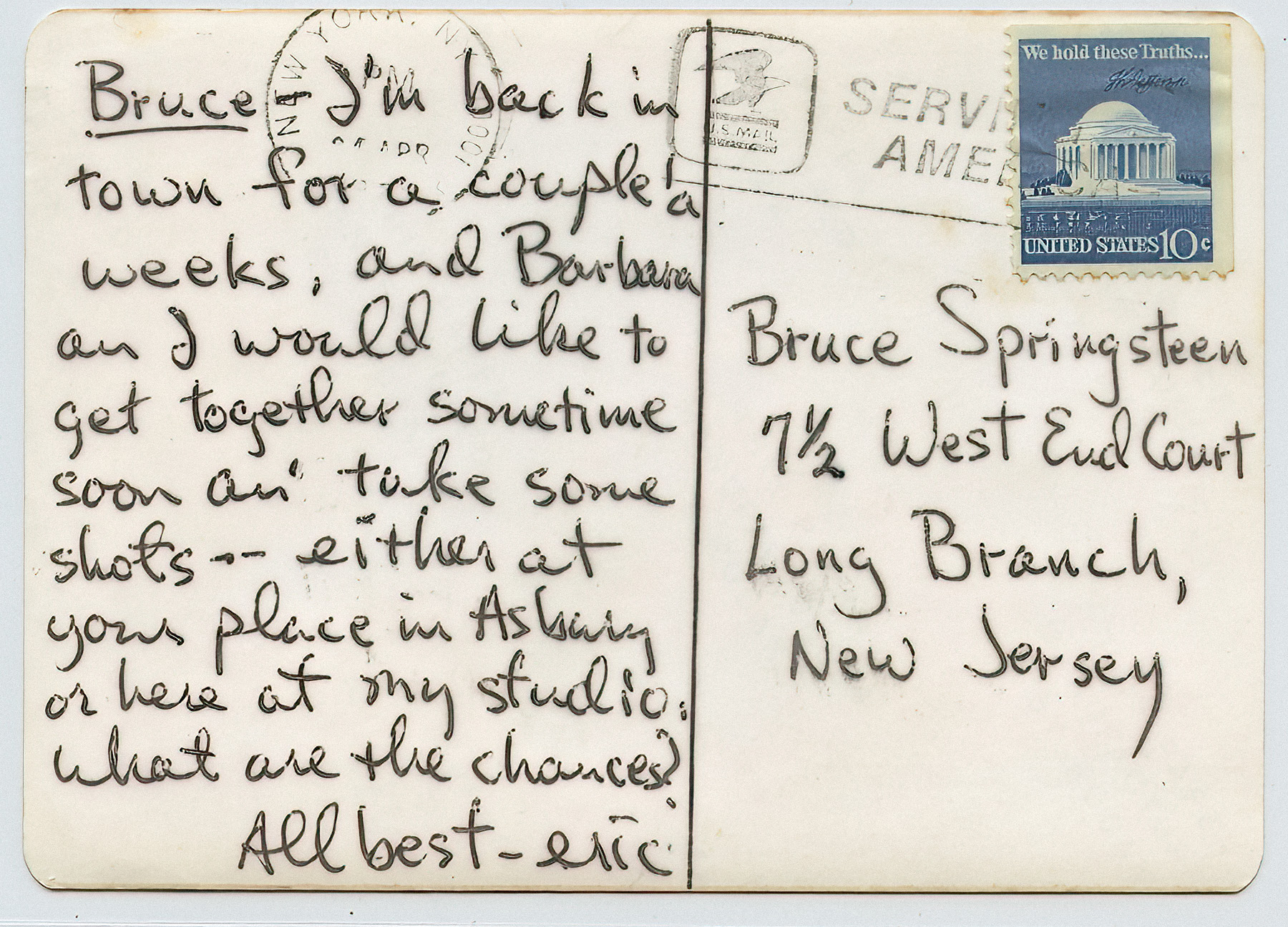

And so at some point that winter of 74, 75, I decided I just gotta go down there and take some photographs. So, I took a subway uptown, took a train down to Asbury, and then I knocked on the door at 7 1/2 West End Court and there was no answer. And we were supposed to get together. And what had happened was that Karen Darvin, whom he had met down in Austin, had come up to New Jersey, and just shown up a little while before I did or the day before I did.

So I went to a phone booth not knowing that, and called the only number I had and finally Bruce answered. Then he came out and said, 'So what do you wanna do?' He said, 'Why don't we go for a ride?' So we got in his car and we drove around for about 30 minutes while I took photographs. And that was the first time that I had photographed him, really.

I have to ask which car.

It’s the yellow ‘57 Chevy. I'm almost positive it was parked out back of the house, I'm pretty sure. Anyways, we drove around, and I photographed him, and we went down to the boardwalk and I shot some photographs there. And I was, I don't wanna say confused, but I was trying to get a sense, I was very shy myself. I was trying to get some sense of how to photograph him, and get to know him at the same time. And we left it at that. And then I took the train back. And I remember thinking all the way back about how do I do something different?

Some time in early April, I have the exact date written down but I don’t have it in front of me, I think April 10th, April 4th.

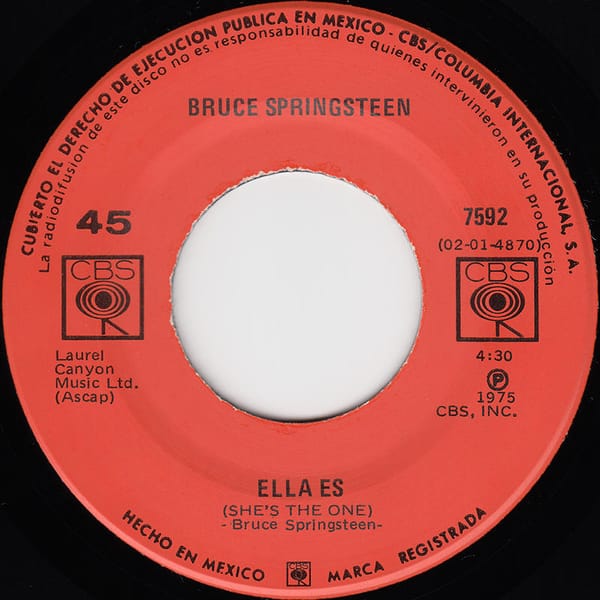

April 4th you sent the postcard.

Yeah. And it was one of those things, I really thought to myself, 'Well, he's never going to answer this.' But the reason I did a postcard was, I was young and I thought to myself, 'Well, there was a postcard on the first album and maybe he's into postcards? So I'll write him a postcard.' And the next thing I know, he calls me up. I've given him my phone number and he calls me up and he said, 'Yeah, come on down.' So I still didn't know how I wanted to photograph him.

And then I realized that they were sort of locked in the studio. I had visited the studio a couple times. I just I just didn't feel like pulling out a camera and photographing there, because I wanted to hear the music first of all. I was an observer and it's one of those times, it's only going to happen once in a lifetime when you can sit there and they don't care that you're there. I mean, looking back, even a day later, a month later, 10 years, 50 years later, you can't imagine that you were actually allowed to do that, but you were actually allowed to do that, but you were.

I decided to get really serious because I knew that they were coming down to the deadline of having to go out on tour again and that the album had to be finished and Mike was really pushing. And at some point, Jon Landau came into the picture. And it became pretty obvious, even though there were no face-to-face confrontations, that Mike saw the writing on the wall. And we didn't know that, we knew nothing about what kind of contract had been signed or anything like that.

We didn't think about those things. But it was becoming obvious that Mike wasn't going to be his manager anymore. And of course that took another year or two of legal wrangling, but I knew that it was sort of a now or never situation. Now, I don't remember how it came to be that, you know, I don't think it was a question of my being chosen, per se. You know, Columbia had assigned David Gahr to photograph Bruce for The Wild and the Innocent. And normally that's probably what would have happened. They would have finished the album and someone would have said, oh, by the way, we need a photograph, you know?

So I had spoken with Mike about it, and I said to him, ‘I want to photograph, take some photographs for the cover,’ but who was I to say that? And it'd be presumptuous to say it's for the cover, but I did. At some point, Bruce and I got together fairly seriously and spoke about it. And he said, ‘Well, one thing's for sure, I want Clarence in the photographs.’ I said, ‘Well, that's fine.’

I didn't ask him why, but given the fact that more than half of the band had completely changed in the last few months and I think he sensed that he had put so much work into this that it was just gonna be Bruce Springsteen. And Clarence had only been with them a couple of years, but he was starting, he and Clarence were bouncing off of each other in terms of their stage presence and the way they acted on stage.

Meola references a Facebook post he wrote last month where he talks about a video from Australia in 2017, where Bruce pulls a teenager out of the audience to play “Growin’ Up,” and how during this interlude, Bruce offers some advice: “I realized it wasn’t how well you played, it was how good you looked doing it.”

“What I said to Bruce was, ‘The best thing we can do is to get in the studio.’ I was very much into Richard Avedon's work at the time, you know, shot against white backgrounds. I knew I had a lot going against me in the sense that I'm gonna take someone who's so used to being on stage with a live audience and I'm gonna bring him into the studio and effectively say to him, ‘Okay, just go through your poses.’

That's what he was saying to that kid, is that you gotta have the moves, you gotta look like a rock star. So he asked me what kind of clothing to bring and I said, ‘Well, do you have a black leather jacket?’ and of course Mike Appel loaned him his and Clarence brought the black leather pants and the black fedora and the white shirt.

At some point, I had gotten the idea of taking them to Ellis Island because I'd heard the lyrics about runaway american dream. I got a phone number for Ellis Island, some Army guy answered and at that time the whole thing was shut down. Ellis Island had been in undergrowth for 56 years, been shut down, and they were just starting to think about how do we preserve this and how do we clean it up. So I just kept getting stonewalled.

Finally I said to Mike, we're gonna shoot in the studio. I've spoken with Bruce about it and we've got to do something. Now, my sense has always been that it was a way for Mike to assert his authority, that it was just that one last straw that he could cling to, that he was going to, you know, in effect, assign the photographer to take the photographs. John (Berg, Columbia Records art director) didn't seem to care at all or know that I was doing this, nor did Columbia. And maybe he did, maybe he didn't, but I have a feeling that they didn't know who to go to other than Columbia and they just said, 'Well, give him a chance.' I really don't know what happened. I've never spoken with Bruce about it and I doubt that he remembers at this point.

Can I just stop you here? You answered a bunch of questions I wanted to ask because when I read that it was a closed set, that no one else was there, I'm thinking, ‘He did not have the clout at that point with the label to close the set.’ But as you're explaining it, I'm assigning attributes to this shoot that were not in play because they weren't touching it. Nobody was involved in it. That's kind of amazing.

Yeah, you know, when I say in that piece (the Facebook essay) that I was in the right place at the right time. I was there and I had sort of informally set up this shoot in the studio and I didn't even have an assistant or anyone to be there. So I had set up all the lights and was loading my own cameras. But you're correct, there was no formal thing where I'd gone to Columbia and said, ‘By the way, I've got this opportunity to photograph this guy, Bruce Springsteen, who happens to be on your label. That never happened. I mean, I walked into John Berg’s office with the prints, and he was, like, flabbergasted. Like, ‘Who are you?’

So they didn’t know. You took the pictures on Friday and on Monday you walked into John Berg's office. None of these people were involved. So it’s not like he had in his mind, ‘Oh, this is going to be a gatefold, so you should make sure to get this kind of shot' – none of that was involved.

None of that. And the funny thing was, I had made a whole bunch of prints, one of which happened to be the cover because it just stood out. And I knew Bruce wanted Clarence. There were a lot of shots that didn't have Clarence in it, but a lot that did. So I tended to concentrate on the ones that had Clarence in it. And I just brought the prints up there. I had gone up there at some point to interview with him.

He sort of remembered me, but I went up in what's called Black Rock (the now-Sony Music building on the corner of Sixth Avenue between 52nd and 53rd Street, so named because of the dark grey granite of the facade). He looked at me sort of whimsically and with a little bit of shock. And he looked through them and he said, ‘Well, these look great, why don't you come back later in the week?’

On Wednesday, I went back there, I don't remember if he called me or I called him, but he effectively said, come on up. And I went up there and that's the first time I saw the cover and I was in total shock when I saw it because I realized it was going to be a fold out, potentially. You knew immediately that it was the cover. They might reject it for some other reason, but he had made an incredible choice in the way it put Bruce on the front and Clarence on the back, you know, and extended the white space to the left for all the credits.

He was facing me, I was facing him. And so he pushes it across the table to me and he says, ‘So what do you think?’ And I looked at it and I said, ‘Wow,’ something like that, ‘This is incredible.’ And he said, ‘Well, I've got to argue with them. It's gonna cost an extra 50 cents a cover to print this. And so we might lose out,’ he said, ‘I've dealt with Bruce before and he always wants something real serious.’ Which made me think of The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle. And that was that.

I don’t know if you have an answer to this, but you’ve said your influences for the cover were Avedon, Daniel Kramer, and I’ve always been curious about what about Bruce or the music that led you in that direction, or was it more of a slow burn of you see one thing, you see another thing, you see a third thing, and suddenly you’re like, oh yeah, that’s what I need to do? Do you remember what that sort of creative math was in your head?

I think what it came down to was, first of all, you know, there are some great photographs for covers, you know, like London Calling, you know, there were the guitars getting smashed, and then, you know, the Beatles walking across the street. But I was, again, I was really into the Bob Dylan thing with Dan Kramer, but also Alfred Wertheimer with Elvis. It was the black and white, even though my whole career has been about color. I just sensed that this needed to be a black and white photograph.

Because also the other thing is that there's no other covers in 1975 except for one that look anything like this. Like nothing else looks like this.

What is interesting, and I've thought about this a lot, I'm trying to remember the name of the guy who is a brother of a late 50s, early 60s singer. And he would go around to all the record labels – Getty Images, for instance, owns his collection – but what he would do is he'd go around to these record labels and ask for all of the 8x10s that were like promo shots. The corny things with Bobby Darin, shot with flash and they're all wearing suits and the Everly Brothers, and it sort of harkens back to that thing where I wanted this to be very artful, very artistic, but at the same time, I wanted it to be super clear who these guys were.

This is about rock and roll. We need the guitar in there, we need the saxophone in there. We gotta see the instruments, we need the black leather. It's gotta be black and white. And when Bruce said he wanted Clarence in there, we were on the same page. And so I think that's where the sensibility came from.

I also wanted a lot of control. And the hardest thing for me was when that door opened and they stepped off the elevator and here I am all alone. And, I know they've just come from the studio and I've got to somehow suddenly prove that this can work. So the first few minutes were awkward in the sense of I didn't wanna stand there and say to them, 'Okay, so you lean to the left and you lean to the right.' I just wanted that to happen.

And Clarence, to his immense credit, knew what I was trying to do. And I know Bruce did as well. It's just, it was more of an awkward thing for Bruce to start to get into that because I'm sure that Bruce, over the years, starting way before the Castiles, looked into a mirror and said, 'I gotta stand like this.' And all of a sudden they sort of really got into it, and I mean, it got to a point where they would do four or five poses in literally 30 seconds or less, And then they'd start laughing at it, laughing at themselves, like, 'Oh, this is cool,' or 'This is stupid,' you know?

It became a thing too, where I started to get into it because if you go through the photographs, they range from – I only shot with one lens, a 105mm lens, which is a semi telephoto lens. And I stand back to get them from the waist up. But then I would suddenly walk real tight to them, and there's a couple shots of Clarence and Bruce where I'm cropped in really tight on the two heads.

And they’re laughing. I love that.

And they're just, like I said, come from days of being in the studio, and so we're all laughing and we got into it. And then I say, ‘Okay, let's change the clothes. Take the jacket off, put this shirt on.’ And so we had a drill going on, where every couple of minutes we would change the clothes. And also, Bruce was quite a bit shorter than Clarence. And so I had these sort of milk crates, that wooden crates that he could stand on that boosted him up about three, four inches.

And then as I'm shooting, and I'm not saying this to say it, but I remember that moment when they were doing back to back, Bruce was standing with his back to Clarence and Clarence with his back to Bruce, and then leaning on Clarence as Clarence was playing the saxophone. And then all of a sudden, he leaned on Clarence, and I got a few frames off, and there's a second frame that's almost the cover. I mean, for all purposes, you initially would not tell them apart, except that little sort of impish grin is missing. You know, it's a little different, a little more subdued, but it lasted like two seconds, three seconds, and he held it. You just knew at that point that it was something really special. It took going up to CBS and seeing how John had laid it out to make me realize that that was the moment, you know, that he had seen that.

And the crazy thing is, if you look at it, what makes it work from an art director's standpoint is that space between Clarence's fedora and Bruce's head allows that split to happen.

WOW. Yeah.

So the right side ends up being a square and then he makes the left side into a square.

Wow, I've never ever thought about that before. That's amazing.

Yeah.

And this was only two hours? The shoot was only two hours?

Yeah, it if that. I mean, what happened was, at a certain point, I guess Bruce had, in his own mind, set a time limit for it, and at the same time, you can only do so much. I'd shot probably at that point about 14 rolls of film, 15 rolls of film.

That was my next question, how many rolls of film did you shoot.

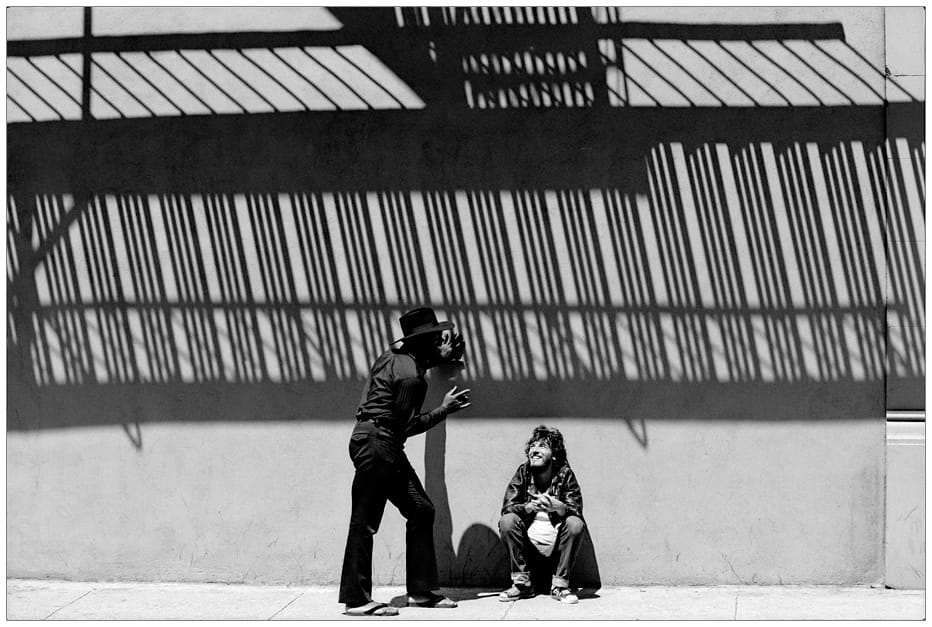

Bruce said, 'So you're done?' or something like that. I said, 'I want to go outside' because I scouted this fire escape and we went downstairs and around the corner. It was a beautiful sunny day and there was this fire escape nearby that had these really great shadows, and so I asked Bruce to stand there.

I shot some shots, and then had Clarence walk by. Of course, all these people in New York are walking by and no one recognizes either of them. And I shot another four or five rolls there. So yeah, it was roughly, they came in somewhere around 10 o'clock in the morning and they left, they got in a cab and went up to the Record Plant around noontime.

And that was it. Did you go to the printing plant at any point? Were you involved in that level of quality control, or making sure your stuff looked good?

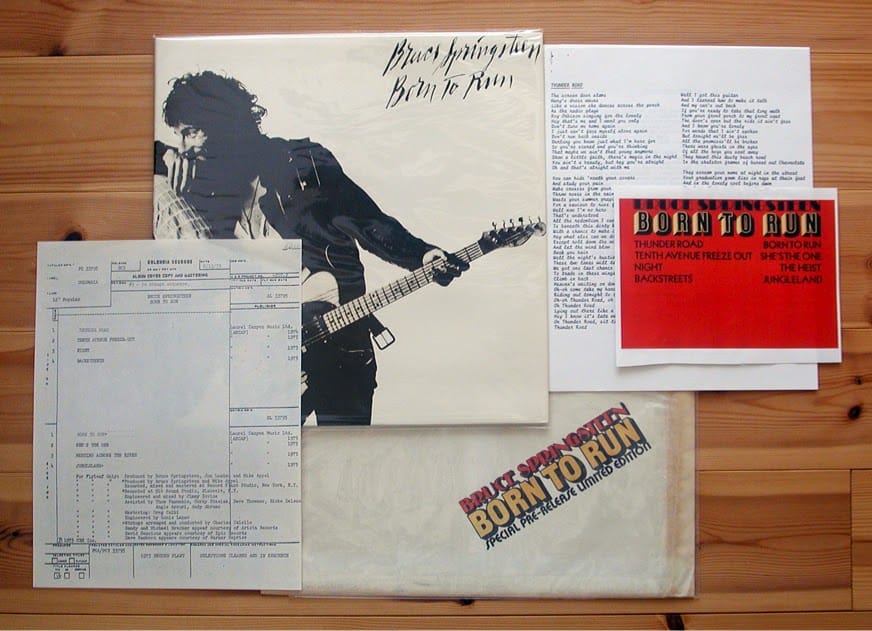

No. What happened was, a couple of things: first of all, when I left John's office having seen that layout for the cover, he was genuinely unsure whether it would become the cover because of the costs and because of Bruce having a say, and I don't think at that point Bruce had seen it. And there were a number of issues also, they ran a second cover and I'm sure you've seen that, where it's sepia colored, and it has the jagged type.

The script cover.

But by that time, there was a buzz going around, you know, and the buzz was the people at Columbia, people like Peter Philbin (Columbia A&R manager) had heard some of the songs and everyone was really excited.

Then I got an assignment, a huge assignment, the biggest assignment I've had in my career up to that point, to basically photograph coffee plantations and go off to Colombia and Mexico and Guatemala and even to Africa. I'd never had an assignment like that. And so I was essentially incommunicado at that point.

Now the original cover is sort of -- I didn't spend a lot of time making these prints because I just figured, ‘Oh, these are gonna be rough prints, I wanna get them up to John Berg,’ and I didn't give much thought to, ‘Oh, they're gonna reproduce from these.’ Because I didn't think they were, you know? And so I go off and I get back almost a month later and they're printing.

And so, you know, that original cover has that really, black and white, very contrasty look. Since then, I've had super high-res scans made of all these images and they have a lot more detail, a lot more openness in the shadows. They look fantastic compared to that. But it was the look, you know? And no, I didn't have a lot of input in that direction. But they liked the way it looked. I don't want to say I've never liked the way it looks, but I certainly would have done something differently.

Wait, so you printed that? You did your own printing of those, the ones you brought to John Berg?

Yeah.

*low whistle of respect*

I will never forget processing that film because, you know, the film developer that I use is called Tetenal Blue, and they still make it amazingly enough. But with that Panatomic X film, it made it look like it was shot on large format, without using large format. It was very, the grain was really, really sharp and crisp. And I remember processing the film and thinking, ‘Oh God, don't fuck this up. Don't screw this up.’ You know, it was just one of those nerve wracking, the whole day, the whole week had been nerve wracking. They had canceled several times, I know you know that.

But Mike was great. If you ask just about anyone who knew Mike at that time, putting aside the contract and what Bruce had signed, if you put that aside, he was beyond a true believer. I mean, here's a guy who tried to get Bruce to – as insane as it is conceptually – Bruce did not have an album when Mike went to the people who were on the Super Bowl and said, ‘You gotta have this guy sing at the Super Bowl. I mean, what would he have sung?

Maybe someday we'll get to hear ‘Balboa Versus the Earth Slayer.’

Well, I have been told that there is a copy of that that someone has, but I've never seen it. And they were very evasive after they told me. And if anyone would know, it would have been this person. So who knows? I don't hear Bruce bring it up very much.

While we're talking about this, so again, I had all these assumptions about the studio before you explained that nobody was there. Why did you pick the music that you picked to play? You had The Stones and Astral Weeks.

I knew that he liked Van Morrison. And I liked The Rolling Stones. Okay. And as it turned out, Bruce loved December's Children. The Stones didn't have a lot of albums out at that point, and that happened to be the one I chose. But it certainly did not help in terms of the poses that they were doing. I mean, no music would have been appropriate. I guess I could have played some of Bruce's music, but --

You wouldn’t have done that. Do you remember the first time you saw the cover in the store?

No. Strangely enough, I don't remember. And it may be that the first time I saw it was up at Columbia. Let me say this. This is a true thing. I don’t believe that I got to photograph it. I mean, it’s hard for me to accept, as silly as that is. I realized how lucky I was to be in the right place at the right time. I mean, just everything came together and it sort of didn’t come together, but it did.

How does it feel to be the person who's responsible for one the most indelible rock and roll images. When I was in high school, everyone had a poster of it. What does that feel like? Yes, it’s Bruce, but you took the picture, you had the vision.

Well, what I think about is if somehow I didn’t take that photograph, there would have been another photograph that someone else took, and we wouldn’t be having this discussion. I do feel fairly strongly, just because a lot of people have said this, when the initial reviews of the album came out, a lot of people referenced the cover photograph. I mean, it pretty quickly became an iconic image. So I'm proud of that.

I still find it hard to square in my mind that I had this push to photograph Bruce. I talk to people in lectures and I talk about the, you know, Latin phrase, carpe diem, seize the day. And I really, you know, was totally enamored of the music and what Born to Run was about. And that Bruce had spent a year of his life -- more -- trying to get every word, every note as perfect as in his mind. And then of course, as we all know, he thought it was horrible, at least until people hammered it into his head that it was a great piece of music.

Have you ever made a song request that he honored?

No, but a number of years after that, three years after that, Joanna and I knew that he was going to be in Tucson, so we flew down there. We weren't married at that point, and I called him up, I got his number from Clarence, I think, and he said, ‘What's going on?’ And I said, ‘Well, Joanna and I are getting married in a couple of days, and would you and Clarence, come to be at the wedding. And so we had chosen this dirt road out in the middle of nowhere and he and Clarence showed up. Well, anyways, that evening he had a show and he dedicated “Backstreets” to us. So I never requested a song, but –

Good flex, Eric. Good flex.

Endless gratitude to Eric Meola for his time.

Born to Run: The Unseen Photos is out of print but still available used in various locations. And a brand new exhibit of Eric's photos from this time period will be at Monmouth University from September 6 to December 18th, and as part of the upcoming Born to Run 50th Anniversary Celebration at the Bruce Springsteen Archives.

*John Prine and Bob Dylan before someone feels the need to explain it to me