The Evolution of Born to Run: "Jungleland"

Side 2, Track 4.

For the 50th anniversary of Born to Run, here's a track-by-track breakdown of the evolution of each of the songs on the record, going in order from start to finish. Side 2, track 4: “Jungleland.”

Before we begin, I want to point out that this essay isn’t about "Jungleland,” but rather meant to chart the path the song took to get to its final album version. That’s because there is so much that can be written about one of Bruce Springsteen’s best and most important songs and I already went down various pathways that aren’t relevant to the assignment. So this is a reminder for myself as much as it is for the reader.

The first documented performance of “Jungleland” took place at the Bottom Line in July of 1974. There’s a recording from the 7/13 show, but we don’t know if it’s the early show or the late show. That almost doesn’t matter here, because what we’re trying to do is get a sense for what an early version of this composition was like.

this should be cued, but if it's not, there are cues in the caption

This isn’t the world’s greatest recording, but I’d urge you to ignore the initial crowd chatter and wait for Bruce to get into the song, because people shut up and the track gets far more listenable. (I almost bailed on it myself initially. Be sure to listen later in the song because you can literally hear the tape transport turning.)

What stands out the most is how immediately recognizable it is to people whose Springsteen fandom doesn’t exist in a world without “Jungleland.” The characters, the setting, the melody, the structure is all largely intact and recognizable. There are small lyric adjustments and edits he’ll make later.

One of the small edits is “The Rat pulls her close, and from the churches to the jails…” That stands out because of other similar edits Bruce made on this record where he stopped trying to make everything into a love story. Also: The Rat and Barefoot Girl waltz down Flamingo Lane. The action matters, it shifts the listener's perspective of the scene.

In the next verse, the key elements are there: the giant Exxon sign, the opera on the turnpike, the ballet in the alley. “The street's alive with tough-kid Jets in Nova-light machines, boys flash guitars like bayonets and rip holes in their jeans." It’s 1974, that could be a veiled reference to what’s going on down on the Bowery but even for Bruce Springsteen it might be a little too early to be locked in to that, and punk rockers weren’t the only ones wearing torn jeans back then. But it’s interesting, especially adjacent to “flash guitars like bayonets.” And “The hungry and the hunted explode into rock and roll bands” could easily be interpreted the same way.

Then there’s an instrumental bridge, but this is much longer and more meandering than the final version, it goes into the motif featured during Clarence’s sax break. It will feel wrong to you but there’s no way to know what it felt like if you heard these early versions. And if you keep listening, the reason this bridge is here is because there are two verses that are AWOL and what we know as the final verse ends up as action in the middle. He adds another chorus, even, and then there’s Clarence playing you out. Bruce whistles. Davey Sancious tinkles the ivories.

The bridge features Clarence, but not in the same way the final version does. The focus goes back to the guitar, which makes sense given the time, the context, what other artists were doing, and what Bruce had done previously in his other epics. And then, we shift into Jazz Odyssey. Where Clarence does get to take the lead again, but in a very weak and AOR kind of flavor, before letting the organ vibe for a bit, and E Street meanders on a collective exploration...and it all starts to feel very much like “Kitty’s Back,” only far less focused, but taking up the same presence in the song that the free jazz interludes of “Kitty’s Back” or “E Street Shuffle” did.

It would be fantastic if we could someday see any handwritten drafts that would show us how he got to this point, and what directions he took and abandoned later. (Once again I wish that the Rock Hall had allowed photographs back in 2011, or that I had taken more detailed notes.) But, based on these early live versions and what we see in the studio in the various Barry Rebo films (which Thom Zimny relied on for his “Down in Jungleland” film he created for the 50th Anniversary Symposium in September of 2025), I’m comfortable asserting that Springsteen’s vision for this track was fairly strong from the outset.

The Suki Lahav Era

There are not a ton of 1974 shows in which we can hear the small variations and changes to “Jungleland” as it evolved as a live number, but the one major change we can definitively document is the addition of Suki Lahav and her violin (and to a lesser extent, her voice). Her first performance with the band was (as previously discussed in the "She's the One" essay) the Avery Fisher Hall performance in October of 1974. But given that we have great versions of the Main Point performance, and also given where that date falls on the trajectory of Born to Run’s history (e.g., not long before the band stops touring and settles into the studio), it is truly an accurate and useful representation of the progression of “Jungleland” and a representation of Bruce’s vision for the piece.

To further bolster this thesis, here’s a studio demo of “Jungleland,” the legendary Take 16, which we heard in the Wings for Wheels documentary. This won’t sound dramatically different to you if you’ve heard any show where Suki performs, whether the aforementioned Main Point or even Westbury Music Fair.

In the Studio

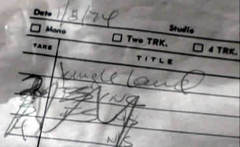

So it’s important to acknowledge this, as per Brucebase:

“In his book Bruce, Peter Ames Carlin claims that from January 8, 1974 Springsteen and the band spent ‘a couple of days fiddling with rudimentary versions of both "Born To Run" and "Jungleland"’ at 914 Studios. However, it is almost certain that Carlin is misinterpreting the handwritten notes of Israeli engineer Luis Lahav, who wrote the date August 1 in the European format (see right).”

I am 100% team Brucebase on this assertion, especially given the timeline.

Unfortunately, whatever versions of “Jungleland” were recorded on August 1 is not circulating. But someone has it: Brucebase says, “They were recorded before David Sancious and Ernest Carter left the band, and were in a distinct arrangement that took inspiration from "Zero And Blind Terry". Then there’s Version 4 (aka Take 16), probably recorded in early 1975, probably at 914 Sound Studios.

Additional takes of “Jungleland” were recorded at the Record Plant; in these demos, you can hear that Bruce is still working through the lyric changes, and trying to figure out the strings. Suki’s tracks survived, and were used on the final version, and as we know, Bruce sang every single note of the sax solo to Clarence to get the performance that he wanted, “Clarence’s greatest recorded moment,” as Mr. S. calls it in his memoir.

As Bruce himself described the ordeal in his memoir:

In a three-day, seventy-two-hour sprint, working in three studios simultaneously, Clarence and I finishing the ‘Jungleland’ sax solo, phrase by phrase in one, while we mixed ‘Thunder Road’ in another, singing ‘Backstreets’ in a third as the band rehearsed in a spare room upstairs, we managed to finish the record that would put us on the map on the exact day our Born to Run tour was starting. That’s not supposed to happen.

These additional demos are interesting, but as we often encounter on these walks of discovery amongst demos, not hugely informative; there’s no great a-ha! moment where some aspect or melody or solo changed the essence of the song. It sure seems like that had been clear to him (if maybe not everyone else) from the outset, and that is the aspect that remains the most illuminating to me as a fan: that a song so fundamental to Bruce Springsteen's body of work was so fully formed so early in its developmental process. It's astonishing, actually.

And given that, one wonders what might have been different had the band not been in the position of having to record inbetween tour dates and stuck in a facility where the piano was constantly going out of tune (amongst other technical issues) and so it was impossible for Bruce and the band to develop momentum. Would the record have been finished while Suki Lahav was still in the States? What would that have meant for the songs, the album, and the E Street Band? It's one of those fascinating what if?'s in music history.

But we have what we have, and it's one of the greatest albums of all time.