"Tonight in Jungleland" : Thom Zimny Takes Us Into the Vaults

About the "Born to Run" 50th Anniversary Symposium

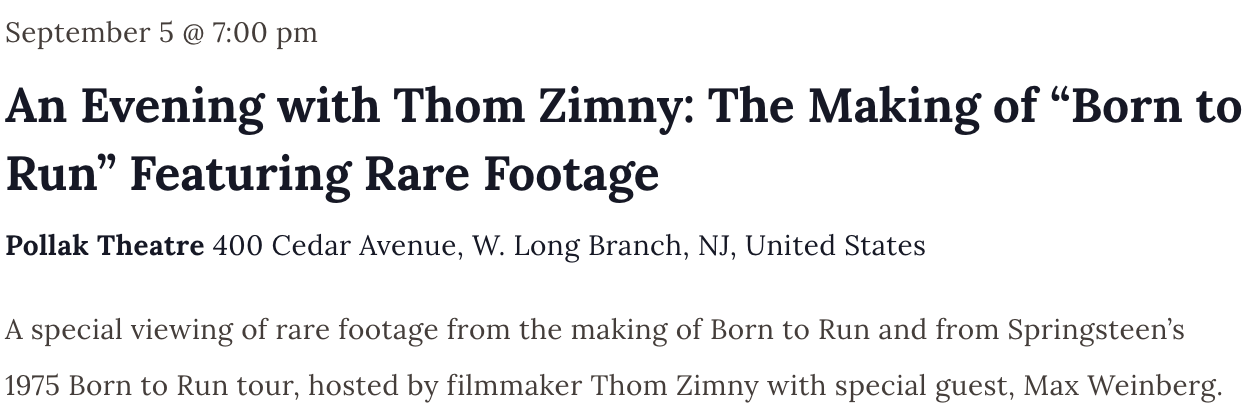

I made it to New Jersey in time to watch whatever magic Zimny was able to extract from the vault as part of the Born to Run 50th Anniversary Symposium held at Monmouth University. I’d been vowing after the last one (in 2024, a benefit for TeachRock where footage from Westbury Music Fair was screened) that I’d never miss one of these again. Rumors (or it was more like fervent hopes) were circulating that we’d get to see “a lot” of Bottom Line footage. But anything uncirculating from 1975 was going to be a gift.

What Zimny put together was – as he himself described it – a form of cinéma vérité. He basically combed through the Barry Rebo footage and pieced together a story about the recording of “Jungleland.” I say “a story” because while all of it happened – it was filmed! – it didn’t necessarily happen in the same order as it was edited together. He was deeply influenced by Pennebaker and Don’t Look Back and his methodology was using small moments to create illusions of full takes. (The quotes are mostly paraphrased here because they had to be written by hand because our phones were pouched, mostly in the dark.) “The vault is a time machine,” Zimny said, more than once. It has the ability to transport both the viewer and, apparently, the editor.

This was a massive undertaking, one that required deep familiarity with the existing footage as well as deep understanding of Bruce Springsteen and his music and how he works. At least with Zimny’s name on the title you know you’re not going to be watching a song and it’s time for the guitar solo and the camera is, instead, on some jamokes in the audience or the horn players dancing. (I’m a big fan of the horn players dancing but don’t show me that over the guitar solo.)

If this wasn’t believable then it would have been disrespectful to the fans. But also, if it wasn’t believable it wouldn’t have made it to the fans, because Mr. B. Springsteen would never have allowed it out. And before you label it pandering or similar, he does not necessarily look great in every frame of this film. By “look great” I don’t mean his physical appearance. But you’ve probably read enough of the books at this point that you are conversant with the stories about how Bruce Springsteen can be somewhat…demanding, while in the recording studio. That reputation is not diminished by this 45 minute film.

They’re up in 914 Sound Studios, which we know because of the giant 914 on the wall. But also because of the presence of both Suki and Louis Lahav. Suki is utterly gorgeous and is also seemingly indefatigable. She picks up her violin to play that early, Spanish-influenced intro of “Jungleland” over and over again, without complaint or even eye rolls. And there are plenty of those from the rest of the band. The best example of this has to be the moment where Bruce makes Roy re-do something that probably didn’t need re-doing, and Roy responds by playing it while holding a cigarette and turning his headphones sideways so one side is right over the center of his face.

The opening shot is of Jon Landau sitting at the console while he pontificates on Jean Luc Godard and how his film about the Rolling Stones recording “Sympathy for the Devil” wasn’t actually all that great. My notes just say “Landau insults Godard” but one thing I want to note for the record – and this may not have been widely known at the time, especially if someone like Landau didn’t know it – that the ending of the film was altered by the producer without Godard’s participation or permission and it ruined his concept completely. But mostly, it was just, “Of course Jon Landau is sitting in the studio dissing Godard.”

Whenever there were shots of Roy Bittan at the piano, all I could think of was all of those stories about how the piano at 914 would always go out of tune. This time, however, we get to watch someone calling for a piano tuner to come in and tune the piano, under a conversation between two people at the board talking about how the piano had gone out of tune again and should we stop them / should we tell Bruce.

Then the piano is tuned and piano tuning is tedious and takes a very long time. This isn’t dead air, this isn’t an error – this is because the piano at 914 going out of tune is legend at this point; it’s a stand-in for all of the problems of being stuck up in Rockland County at this out-of-the-way studio because the band didn’t have money to waste, and this device was an excellent way to communicate all of that backstory.

There’s an attempt to get Clarence to tell a limerick, but he politely declines to do so because it isn’t very polite. Several people would later try to get the band members who were present to tell us the limerick – Tom Cunningham tried to get it out of Boom Carter and David Sancious the next day – but regretfully we did not get the punchline. There’s other levity as well, the band eating dinner in the studio (where Bruce waxes rhapsodically about how everyone in the band agrees that whatever time they’re eating food together is the best time of the day).

There are also shots of Bruce inside the diner next to the studio. (I heard from someone behind me whispering loudly that the diner is still there, but it’s closed. Some day I will make it up to Blauvelt.) All of this is happening between takes and re-takes and additional takes and one more and do it again. The young Danny Federici was there, mustachioed and golden and still with us. Both him and the Big Man seem completely unfazed by anything going on in this footage.

For all that Bruce Springsteen criticizes his early lack of studio know-how, what I got out of this footage was that he had every single note for every single instrument on this record worked out in his head. He knew what he wanted it to sound like and what he wanted it to feel like. He conducts Max, he tells him to not play in a certain style when the band were playing certain notes (Max afterwards: I don’t know notes, I’m a drummer), he was demonstrating to Suki Lahav how he wanted her to play by using a drum stick as a makeshift violin bow.

A note reads, “I’m shocked Bruce is still alive.” I cannot tell you if someone said that on screen or if it just came from my brain. Either way, I stand by the sentiment. There was a discussion about “E Street Shuffle,” someone offering their viewpoint that it wasn’t meant to be what it became. “Shuffle was an afterthought, everybody loves it, and so we made it into a whole thing.”

Then the footage switches to the band onstage, the camera centered at the back of a room that could only be the Bottom Line, taken from the 8/16 late show. We didn’t even get that confirmed until Zimny was a few minutes into his chat with Erik Flannigan but it was such a distinctive and legendary room for me personally that I’m not going to forget what it looked like any time soon.

And this performance footage? Take what you think how amazing it is and throw it out because it was better. Not that it’s super high quality – it’s one camera, centered up high at the back of the room, pointed at the stage at a room that was dark – it was painted black inside – and aimed at a man who thought spotlights were the devil. It’s extraordinary. It wouldn’t matter if it was on flip cards. It’s “Jungleland” performed a couple of weeks before the record comes out, about a month after they finished recording it at the Record Plant.

Bruce doesn’t have a guitar on so he doesn’t know what to do with himself at all. He also does not know how to move around onstage during the bridge -- it’s jagged and awkward and other words you would never use to describe Bruce Springsteen onstage -- but at the end, when he collapses at the foot of the microphone stand, you are just absolutely stunned. It’s still unbelievable, 50 years later.

Zimny and Max Weinberg joined Erik Flannigan to talk about the footage afterwards. Zimny explained that he'd spent so much time with the footage that he knew every single moment, and that there were moments that he could spot in his Letter to You film and this footage and he has always gotten the small moments so incredibly right. As a viewer of his work, I'm confident that he's not ignoring the great or amazing moments. I am never yelling "GUITAR PLAYER" at the screen.

I kept thinking of this particular moment in Letter to You, and I can't remember if it was in something that Chris Phillips wrote or it was in a conversation I had with him, it's that Zimny sees these moments, understands their importance, and always makes sure that we, the fans, see them as well.

Max once again told the story about him missing Bruce’s cue and once again attributes it to the wrong night. (He insists it was the night of the radio broadcast and we know it was not that night because we have a tape, so I wish someone would just explain that to him once so the wrong info doesn’t keep getting transmitted repeatedly.) He also talked about the scenes in the studio and how all he kept thinking was, “I hope I don’t get fired.” Similarly, there’s a shot where Bruce is trying to get the end of the song done and the camera is focused intently on him, and he looks straight at it and says, “You can’t do this while I’m doing this” (or similar, again, a paraphrase). Flannigan asked Zimny if he had ever gotten a similar look from Bruce and his response was, “I fear this.”

I was kind of hoping we’d get more songs after the talk but I’ll guess that the Bottom Line footage is probably very difficult to work with for all of the reasons noted above. But despite its inherent limitations I would still really like to see more of it before I die and I think most of us would agree with that sentiment. Maybe some day we’ll be able to walk into the Springsteen Archives and push a couple of buttons and be able to sit and watch it all for hours. A girl can dream.